THE CAPE HATTERAS LIGHTHOUSE

(The following is from a National Park Service

handout)

The days of the blue-uniformed lighthouse keeper - checking his whale oil supply, slowly climbing the tower to clean his lenses - have passed forever. Yet the lighthouse he so faithfully attended remains on duty. Built of bricks to serve as a functional warning device and possessing a very special beauty noted by seaman and landlubber alike, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Stands on a spot still dreaded by mariners. Its needle of light still guides them as it has for over 100 years.

The picture above shows a monument to the commitment of the Lightkeepers.

Their names are etched in the granite stones (foreground) that were part

of the original 1870 foundation until the lighthouse was relocated in 1999.

This monument was moved in 2015 due to repeated storms burying and tossing the

stones. They are now near the pavillion outside the Gift Store, and were

dedicated as the Keeper of the Light Ampitheatre.

HISTORICAL BEGINNING

Lighthouses have a long and colorful history. The earliest recorded date for a regularly maintained light that guided mariners is 600 B.C. Even the ancient Egyptians built light towers; priests tended the beacon fires. By the 18th century open fires on platforms at or near dangerous points protected the coasts of Europe. Today the lighthouse is a steel or brick structure, whose electrically timed and automated light probes more than 20 miles out to sea, still warning of hidden reefs and deadly shoals that menace the navigator.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse stands on a spot of eastern North America dreaded by sailors since the 16th century, when European ships regularly bagan sailing or "coasting," the Atlantic seaboard. A warm offshore current, the Gulf Stream, flows north at about 4 knots and veers eastward north of Cape Hatteras. Spanish treasure fleets returning from the mines of Mexico and Central America made good use of this northbound current on their voyages to Spain. Southbound vessels followed an inshore counter-current of colder water, the Virginia Coastal Drift.

These might have been two very efficient marine highways, exept that at Cape Hatteras the Gulf Stream pinches down on the inshore current and forces southbound ships into a narrow passage around Diamond Shoals, the submerged fingers of shifting sand that jut more than 10 miles out from the Cape.

More than 500 ships of many nations, trying to find their way around these shoals, have foundered at or near Cape Hatteras, earning for the area its sinister reputation as the "Graveyard of the Atlantic." The absence of natural landmarks along the Carolina Coast added to the navigator's risk, as he was drawn dangerously close to shore to get a bearing.

THE FIRST TOWER

Recognizing the very real danger to Atlantic shipping, Congress authorized the construction of a permanent lighthouse at Cape Hatteras in 1794. It took almost ten years before a "light was raised" in October, 1803. Built of sandstone, 90 feet high, the tower was a start, but only a start, in providing the protection needed in these hazardous waters. A major problem through the years was illumination; the small whale oil lamp did not penetrate the darkness beyond the shoals. Storms shattered the windows and broke the lamps, putting the light out for days at a time.

Complaints were numerous and vocal. In 1837, the Captain of a coasting vessel reported that "...as usual no light is to be seen from the lighthouse." In 1851, Lieutenant H. K. Davenport, Skipper of the mail steamer Cherokee complained, "Cape Hatteras light, upon the most dangerous point on our whole coast, is a very poor concern ..."

Creation of the Lighthouse Board in 1852 drastically improved the conduct of the lighthouse operations in the United States. Composed of men familiar with the problems involved, the board answered directly to the Secretary of the Treasury, and soon acted to correct the deficiencies at Cape Hatteras. Among the first corrections was to raise the tower to 150 feet and to install a First Order Fresnel lens. Developed in France by Augustin Fresnel, the lens utilized prisms and magnifying glasses to intensify a small, oilwick flame into a powerful beacon of many thousands of candlepower. The improvements made the Cape Hatteras light one of the most dependable on the coast.

Cape Hatteras light burned steadily for only seven short years before the holocaust of the Civil War extinguished it again. Confederate forces wanted the lighthouse destroyed to deprive Federal vessels of the beacon. In 1861, Union forces managed to save the tower, but retreating Confederates took the Fresnel lens with them. Although the light shone again in 1862, the tower had been damaged and the Lighthouse Board recommended extensive repairs. Studies showed that it would be less costly to build a new tower than to repair the old one, and in 1867 Congress appropriated $75,000 for a new Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Because of erosion danger, it was built 600 feet north of the original tower.

THE SECOND TOWER

The present brick tower, erected in 1869-70 by the Lighthouse Board, cost more than $150,000. Major George B. Nicholson, Assistant Engineer for the Fifth Lighthouse District, supervised the construction. Both this tower and the original structure were built before the modern pile-driver was perfected; both therefore were set upon "floating foundations." This means that two layers of 6" x 12" yellow pine timbers were placed crossways in a pit below the water table. Always submerged, the timbers were protected from rot and preserved through the years. Recent examinations showed no deterioration of these century-old beams.

A new Fresnel lens and oil lamp were installed and a light first flashed from the tower on December 16, 1870. The old tower, no longer useful and in danger of falling, was intentionally destroyed. The final "touch" for the new structure was the distinctive black and white striping ordered by the Lighthouse Board in 1873 to make the tower "a better daymark on this low sandy coast." This practical application of paint turned an ordinary tower into one of the most striking and beautiful structures on the Atlantic Coast.

THE LIGTHOUSE TODAY

When the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was built in 1870 the tower stood 1,500 feet from the sea. By 1935 erosion had progressed to the point where the waves washed around the base of the tower. All efforts to halt erosion failed and the lighthouse was abandoned and replaced with a skeleton steel structure a mile northwest of the brick tower. In the late 1930's the erosion trend halted. These natural tendencies plus beach erosion control work by the Civilian Conservation Corps permitted the return of the light from the steel tower to the lighthouse on January 23, 1950. The National Park Service acquired ownership of the lighthouse when it was abandoned in 1935. In 1950, when the structure was again found safe for use, new lighting equipment was installed. Now the Coast Guard owns and operates the navigational equipment, while the National Park Service maintains the tower as an historic structure. The Hatteras Island Visitor Center, formerly the lighthouse's Double Keepers Quarters, elaborates on the Cape Hatteras story and man's lifestyle on the Outer Banks. Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the tallest in the United States, stands 208 feet from the bottom of the foundation to the peak of the roof. To reach the light which shines 191 feet above mean high water mark, Coast Guard personnel must climb 268 steps. There were 1,250,000 bricks used in teh tower's construction.

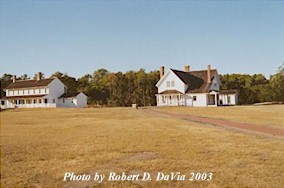

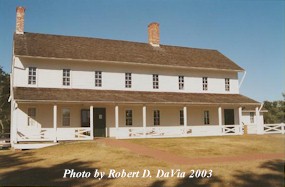

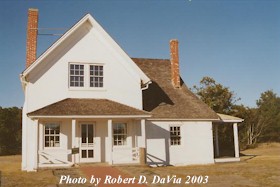

The picture above shows the Double Keeper's Quarters (on the left)

and the Principal Keeper's Quarters (on the right). They are now used as

Hatteras Island Visitors Center and the

Ranger Office. The two pictures

below are closeups of the respective houses.

THE LIGHT

The Lighthouse Service changed the illuminant to an incandescent oil vapor lamp in 1913. Twenty years later, in 1934, the Service electrified the Cape Hatteras light. A new lighting device was installed in 1950. The present, more powerful device was installed in 1972. The illuminating equipment consists of a rotating beacon with two 1000-watt lamps. Each lamp produces a beam of 800,000 candlepower visible in clear weather for about 20 miles. It appears from a distance as a short flash at intervals of 7.5 seconds. Under especially favorable atmospheric conditions the light has been observed 51 miles at sea.

THE LENS

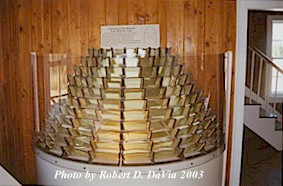

A section of the Original Cape Hatteras Lens on display in the

Hatteras Island Visitor Center, formerly the lighthouse's Double Keeper's Quarters

The type of mechanism changed several times over the years. With the installation of the Fresnel lens in 1854, the light changed from a fixed beam to a revolving flare. To rotate the lens, a weight descended sloly from the top of the tower into a well at the base, engaging a series of gears which turned the beacon. It usually took 12 hours to make a complete decent. The keeper than re-wound the apparatus for another cycle. When the light was electrified in 1934, this rudimentary device was no longer necessary. Today electricity provides the rotationg power and a phot cell turns the light on and off. Although the mechanism has changed, the light itself has remained white.

OFF SHORE HELP

Even with the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse as the primary aid to navigation in the area, secondary warning devices were needed further out on Diamond Shoals. Such devices were considered as early as 1803. After storms ruined repeated attempts to erect a tower, the Lighthouse Service decided to anchor a lightship at the outer limits of Diamond Shoals. Through the years three lightships have been placed on station; the first dropped anchor in 1824, but was broken up in a gale three years later. Lightship #69, the first to be named "Diamond", took its position in 1897 and remained until 1918 when gunfire from a German submarine sank it. The third, again named "Diamond," remained on the shoals until 1967, when a Texas tower-type structure replaced it.

Return to the North Carolina State Page

Return to the: Alphabetical Listing or the Listing by States